|

|

At the turn of

the century (19th to 20th), scientists had

thought they had the universe pretty well figured out.

Newtonian physics was strongly entrenched, describing the

motion of objects in the heavens and on earth like clockwork.

A bolster to this Newtonian worldview was the discovery of

the 8th planet in our solar system - Neptune.

In the mid 19th

century, Uranus, then the farthest known planet from the Sun,

displayed unexpected changes in its orbit.

In 1845 – 46, French astronomer, Urbain Le Verrier, deduced

that these perturbations were due to the gravitational pull of a

more distant, yet unknown, planet.

Le Verrier transmitted his calculations to a German

astronomer, Johann Galle, who, when observing, located this new

planet in a matter of hours. Score

another one for Newtonian physics!

Flush from the

victory of discovering the 8th planet, Le Verrier tackled

another mystery – the unexplained anomalies of Mercury’s orbit. If

Newton’s law of gravitation was correct (and predicting the

existence of Neptune seemed to be concrete proof that it was), Le

Verrier postulated that some planet inside Mercury’s orbit

disturbed it. Le Verrier

suggested the name of this hidden planet as Vulcan, after the

Roman god of fire.

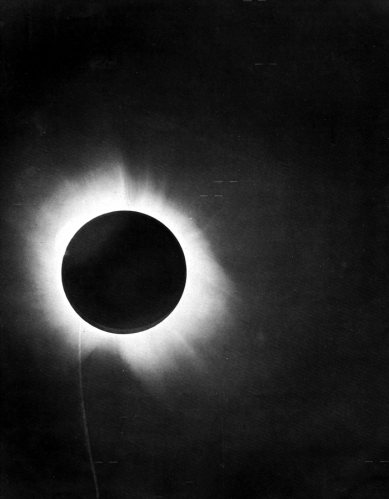

As Vulcan would, in theory, be closer to the Sun than Mercury, it

would be very difficult to see from the Earth.

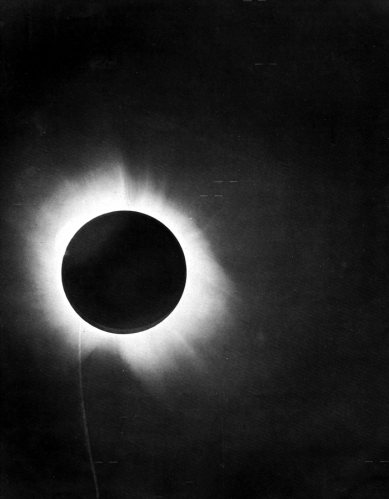

Viewing would be possible during a total solar eclipse, when

any sizable object near the Sun could be more easily seen whereas it

wouldn’t be detected otherwise.

But total eclipses were infrequent and only lasted for a few

minutes.

Another opportunity would be a transit, when Vulcan would pass

directly between the Earth and Sun, appearing as a dark circle on

the Sun’s surface, moving rapidly from west to east in a straight

line. Since the time of

transit for a planet could not be predicted until its orbit was

accurately known, the first sighting must be by luck.

In 1845, French amateur astronomer, Dr. Lescarbault had observed

a dark object against the Sun, which he later felt must have been

Vulcan. From

Lescarbault’s observation, Le Verrier estimated that Vulcan’s

distance from the Sun was about a third of Mercury’s and it must

have a period of revolution about 19.7 days.

He estimated the diameter of Vulcan to be a little over half

the diameter of our Moon and a mass of one-fourth that of our Moon. Though

not large enough to explain all of Mercury’s perturbations, Vulcan

might be part of an asteroid belt, similar to the one between Mars

and Jupiter.

With these proposed orbital parameters, the only time Vulcan

could be seen in the sky in the absence of the Sun would before

sunrise or after sunset at ten-day intervals.

The bright twilight would make the sightings difficult; hence

that explained why Vulcan had not been detected for so long.

Le Verrier calculated the times of future transits and

astronomers began watching for them.

Unfortunately, astronomers did not find Vulcan where it was

supposed to be. Reports

came in of sightings of Vulcan from time to time.

In each case, a new orbit was calculated and new transits

predicted, yet nothing concrete came of it.

Therefore, the existence of the planet Vulcan was being

questioned – some astronomers insisted it was real, others denied

it. When Le Vierrier

passed away in 1877, however, he firmly believed in Vulcan’s

existence.

In 1878, a solar eclipse passed over the western United States as

American astronomers engaged, again, in the search for Vulcan.

Most of the observers saw nothing, but two astronomers

reported sightings. The

deduced attributes of Vulcan, though, could not account for the

perturbations of Mercury. Also,

the disputed accuracy of Vulcan’s location was insufficient to

calculate its orbit. Hence,

without reasonable ephemeris, the observations could not be

repeated.

At the turn of the century (19th to 20th),

photography was coming of age, so that astronomers could take

photographs and study them at their own pace.

The objects observed inside Mercury’s orbit were so dim and

calculated to be so small that they could not account for the

perturbations of Mercury – which steadfastly flaunted Newton’s

Laws. Vulcan still

eluded the astronomers and the mystery of Mercury continued.

|

|

|

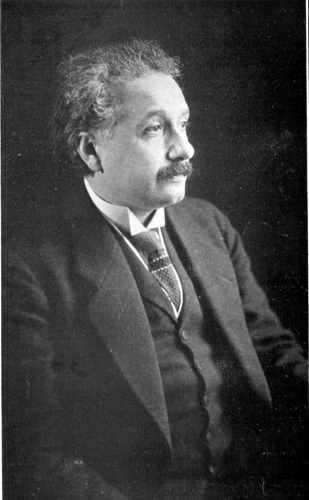

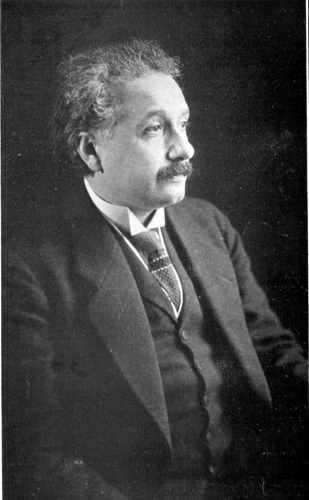

Finally, Einstein literally entered into the equation.

Yet, Einstein’s resolution of the Mercury anomalies was

totally unexpected.

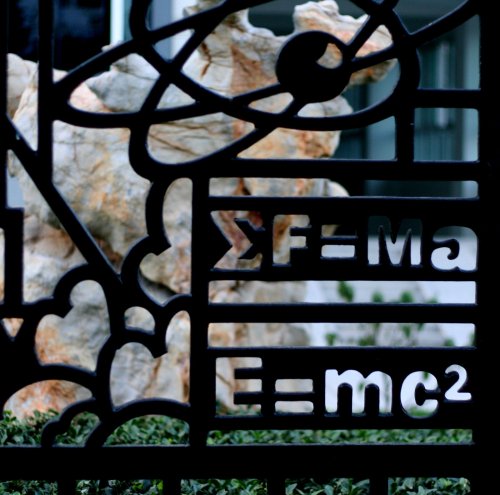

In 1915, Albert Einstein solved the mystery in his General

Theory of Relativity. In

General Relativity, gravitation was an extension of Newton’s laws,

which simplified to Newton’s laws under most conditions.

It was only in the extreme that Newton’s laws break down

and Einstein’s equations provide a better model.

And Mercury’s orbit, which was so close to the Sun, was one

of those extremes.

Einstein’s equation E = mc2 put

forth the equivalence of a large amount of energy to a small

quantity of matter. The

enormous energy of the Sun’s gravitational field interacting with

nearby Mercury was equivalent to the mass of a small planet.

Einstein’s calculations showed that the effect of the

Sun’s gravitation field accounted for the perturbations of Mercury

as well as smaller perturbations of planets farther out.

Since this revelation, most astronomers have abandoned the search

for Vulcan. A few,

however, were convinced that not all the alleged observations of

Vulcan were unfounded. Some

still believe that objects inside Mercury’s orbit may exist, such

as previously unknown comets or small asteroids. Today,

the search continues for the so-called Vulcanoid asteroids, which

may exist in the region where Vulcan was once sought.

Einstein’s theory of General Relativity seemed to have

vanquished the hidden planet Vulcan from our solar system – for

now. Yet, as long Star

Trek is in our consciousness, the home world of Mr. Spock will

live long and prosper!

|